Many of today’s Syracusans, especially those who have lived here for a bit, might recall that our city’s namesake is an ancient town on the Italian seacoast in Sicily. The Italian immigrants that settled in Syracuse, New York, however must have wondered how this upstate locale wound up with the name of that Sicilian town.

In some regards, it is not surprising, but in the case of Syracuse, it has an interesting tale and a bit of a twist.

Today, names of communities like Lysander, Pompey, Cicero, or Marcellus are second nature to local residents. No one usually ponders their origin. But, on occasion, an area student studying ancient history or literature, will be surprised that the name of his or her town was being used by some Roman or Greek citizen centuries ago. In fact, classical history and localities formed the identity for many Onondaga County places.

Central New York was surveyed and divided up for non-Native settlement after the American Revolution. Treaties between New York State and the Iroquois, controversial to this day, removed the Onondaga Nation to a small, defined territory south of Onodnaga Lake. The rest of the surrounding lands were divided into townships, then further divided into. of Each of the townships was to comprise100 lots of 600 acres. Names for the Military Tract’s 25 townships were decided by state officials.

As populations increased in the late 1790’s and early 1800’s, local civil governments were formed within the Military Tract. Some of these first towns decided to carry on the names of the original survey designations.

The late 18th century was an era when learned citizens were quite enamored with ancient Greek and Roman culture. For example, Thomas Jefferson was inspired in his enthusiastic architectural pursuits by classical Roman buildings. His famous Univeristy of Virgina Library was modeled after the Pantheon in Rome, as was his own home, to a degree at Montecello. And Americans, proud of their young democratic republic, readily accepted associations with ancient places in Greece and Italy.

Men like John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, were superb classicists — they could read both Latin and Greek fairly well and knew Greek and Roman literature, history and philosophy rather thoroughly. Just as importantly, from the time they went to school, they saw ancient Greek and Roman statesmen as models to be emulated in their own careers as lawmakers, civic-minded leaders, public figures of responsibility. This influence spread down to local civic leaders, men in Central New York like Joshua Forman, a graduate of Union College in Schenectady who moved to Onondaga Hollow at the age of 22 in 1800, with his young bride, and opened a law practice in this frontier setting, near the Onondaga County seat on Onondaga Hill.

Syracuse owes its origins to a turnpike, the creek, and a mill. Its beginnings were centered near Clinton Square. But the land, at first, was not prized. It was low and dominated by an unhealthy, smelly and discouraging cedar swamp. Places like Manlius, Pompey, and Geddes were well underway before anyone showed much interest in what would become downtown Syracuse.

The catalyst for change became the state’s need to raise money for improving the Seneca Turnpike’s connections to the salt works. In 1804, the legislature authorized selling 250 acres of the salt reservation for revenue. James Geddes surveyed the parcel and included a stretch of Onondaga Creek and its water power potential as an incentive. Residents at Salt Point and Onondaga scoffed at the thought of anyone investing in a swamp. But Abraham Walton, a land speculator and Utica attorney, bought the acreage. By 1805 he had a mill erected where the improved road, today’s Genesee Street, spanned the creek. Another road, now Salina Street, crossed nearby on its way to the salt works..

Walton laid out a small settlement and sold a lot at the corner of Salina and Genesee to Henry Bogardus. The latter opened a tavern in 1806 and the intersection took on the informal name of, Bogardus Corners. Soon a few simple houses joined the mill and tavern. After a few years, ownership of the inn passed to Sterling Cossitt of Marcellus, and the location was re-named Cossitt’s Corners. The nucleus for Syracuse was being formed. But Plagued by the unhealthy nature of the surrounding low lands, anemic Cossitt’s Corners grew very slowly.

Joshua Forman, the visionary, the entrepreneur and the ambitious, set his sights then on the struggling, swampy surrounded settlement in the middle, at Cossitt’s Corners. Around 1815, Forman and a handful of partners formed a land company to buy out Walton’s remaining interests in the tract surrounding Clinton Square. Forman continued to be a strong advocate for the construction of the Erie Canal and helped guide that revolutionary venture into being through his effective lobbying. Construction of the Grand Canal began at Rome, NY in 1817 and the chosen route was headed for Cossitt’s Corners.

But personal problems arose for Forman in 1818 while the canal was still in its early stages of construction. The Bank of the United States had overextended its credit, called in loans from state banks, which, in turn, called in their loans on the heavily mortgaged lands they had financed. Forman and his land company, apparently, were overextended and faulted on its mortgage and their holdings in what would become downtown. The land was sold in a Sherriff’s auction in October of 1818. Fortunately for Forman, the highest bidder was a partnership that included his brother, William Sabine. The new owners turned around and hired Forman to be their agent, so he was able to maintain his management of the land that would become downtown.

Some residents, meanwhile, had thought it might be good to secure a formal post office designation for the little Cossitt’s Corners settlement and proposed Milan, an Italian city controlled for several centuries by the Roman empire and declared the capital of the Western Roman Empire in 286 AD. However, a settlement named Milan over in Cayuga County already had a Post Office. That settlement changed its name to Locke in 1817, but in 1818, the state legislature created the town of Milan in Dutchess County and it grabbed a post office designation in August of 1818. Milan was just not available for Cossit’s.

Forman was continuing to work tirelessly to promote his adopted community. He definitely felt the little crossroads needed a more formal name, one appropriate to its anticipated future as a great city. Milan was not available, but Forman was the agent for the land company that owned most of the area. Additoinally, Forman was having a survey conducted, and streets laid out in 1819. That year, he also moved from the Hollow to his work in progress. So Forman made an executive decision and chose “Corinth.” Corinth was the name of an ancient city in Greece. In classical times, Corinth rivaled Athens and Thebes in wealth. We may know of it more now from the two books First Corinthians and Second Corinthians in the New Testament.

Construction on the canal had begun in 1817 and the middle section was completed by 1820. And sure enough, it flowed right past Forman’s doorstep. Surely, now was the time to get that formal post office established. The application was made to the federal government for the name Corinth.

Unfortunately for Mr. Forman, Cossitt’s had missed the boat again. In 1818, a new town at the northern edge of Saratoga County, along the Hudson River, had been created called Cornith and it had a post office

Forman and his cohorts were not trying to create a new political entity. Cossitt’s back then was formally part of the Town of Salina. They just wanted to establish a post office for convenience. A committee was formed to come up with a new name. John Wilkinson, another newcomer from Onondaga Hollow and a lawyer protégé of Forman’s, had agreed to be the postmaster once it was established and it was he that would suggest “Syracuse.” Why that, well

As we know, Americans in the early 1800s were quite enamored with using ancient Greek and Roman names to identify the new towns in their young “democracy.” Siracusa, Sicily was founded in 734 BC by settlers from Greece. It has a rich history, one including the great mathematician, Archimedes, who called it home. It was conquered by the Romans in 212 BC despite a fierce defense put up by the Greeks. In fact, legend that in has it that among other creative edevices, Archimedes built a giant mirror that was used to deflect the powerful Mediterranean sun onto the sails of the Roman ships, setting fire to them.

But, in addition to its association with great Greek and Roman history, it was John Wilkinson’s fascination with its geography, however, that inspired him to make the suggestion.

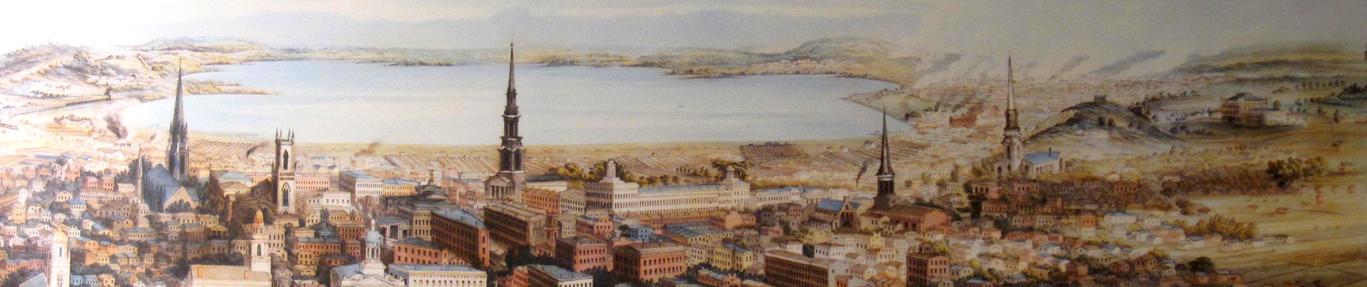

Siracusa, or Syracuse in its English version, was a city that faced water. Wilkinson thought of Onondaga Lake. There were hills surrounding it. Same here in Central New York. Nearby there were evaporating flats making salt from seawater, and an adjacent settlement called Salina. Wilkinson could not ignore the similarities.

This is an Original Map of Siracusa, Sicily dated 1839. It gives us some idea of what early Syracusans might have known about the ancient Greek city that inspired the name for their home in upstate New York. This detail shows the “saline” solar evaporating pans or flats located near Siracusa.

In fact, today, salt is still made near the western coast of Sicily has it has for centuries, by Evaporating waters from the Mediterranean Sea by the solar method.

and there even is a Salt Museum located near there.

But what drew Wilkinson’s interest to Siracusa in the first place?

Would you believe the connection was a 20-year old future prime minister of England titled the 14th Lord of Derby?

While a student at Oxford in 1819, Edward Stanley wrote a lengthy poem, in Latin, about the mythology and history of Siracusa, winning a prize for it at Oxford. In 1819 he was awarded the Chancellor’s Latin verse prize for his poem Syracuse. Wilkinson stumbled upon the poem in a friend’s library in New York City. It caused him to research Siracusa, which was fresh in his mind when the need for our future city’s name arose.