On August 29th 1962, the New York Central Passenger and Freight Station on Erie Boulevard closed due to declining passenger traffic. Originally opened in 1936, the station was built to service the new elevated New York Central Railroad tracks. Eventually, a new station opened on Manlius Center Road in East Syracuse. Initially the abandoned railroad station became a foreign automobile dealership. Later, it was converted into the Greyhound Bus Station. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 11, 2009 and is now home to Time Warner Cable.

Here’s a history of the station from Great American Stations

“The New York Central (NYC) Railroad left its monumental structure downtown for a smaller building it opened in 1962, due to the NYC’s right-of-way through Syracuse being appropriated for the construction of the I-690 highway. The East Syracuse station was a one-story building sufficient to the minimal passenger traffic of the day. The Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council had considered creating an intermodal facility as early as 1991, when that organization published a project feasibility study; eight years later, this new facility opened. Funded by the Federal Transportation Administration, the Central New York Regional Transportation Authority, the New York State Authority and the New York Department of Transportation, the regional transportation center cost approximately $14 million.

The older station suffered weather and water damage. After a fire in 1996, Greyhound, its sole occupant, largely ceased using the interior of the older station building and sold it to Time-Warner Cable in 2001. Time-Warner invested in a $6 million restoration of the station building and adapted its interior to the needs of television and radio studios while retaining much of the historic character. The station was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 11, 2009. The neighboring freight complex, stretching underneath I-690, has changed hands several times since 1996 but remained in use by light industry.

The older station suffered weather and water damage. After a fire in 1996, Greyhound, its sole occupant, largely ceased using the interior of the older station building and sold it to Time-Warner Cable in 2001. Time-Warner invested in a $6 million restoration of the station building and adapted its interior to the needs of television and radio studios while retaining much of the historic character. The station was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 11, 2009. The neighboring freight complex, stretching underneath I-690, has changed hands several times since 1996 but remained in use by light industry.

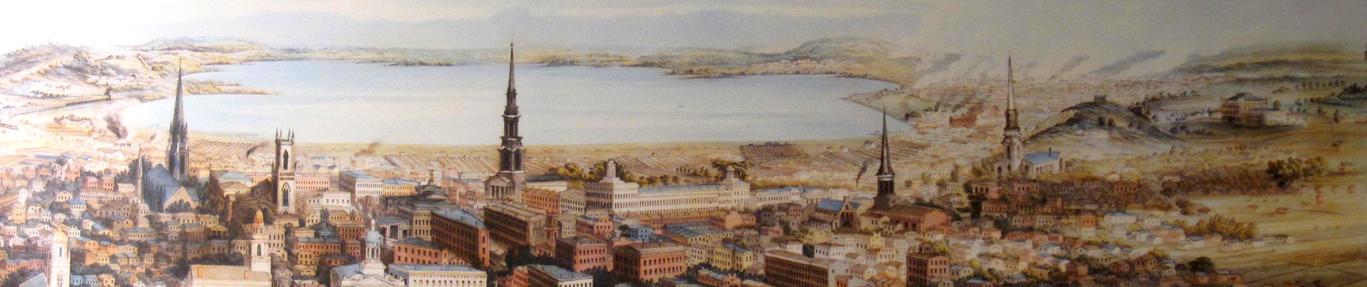

Europeans first saw the Syracuse area when French Missionaries briefly visited the Onondagas who settled just to the south of Lake Onondaga in the 1600s. At that time, what would become the city’s downtown on the south end of the lake was a swampy area watered by briny springs. From the late 1700s through the early 20th century the springs, which tapped into halite beds in the underlying shale rock to the south of the city, were developed into a major economic engine for Syracuse. This city became known as “Salt City,” and at one time the source of much of the salt used in the United States.. James Geddes, salt producer, politician and engineer, with Joshua Forman, an attorney, convinced the state legislature to allow the creation of a canal from Albany west through Syracuse; and Geddes became one of the Erie Canal’s principal engineers. By 1830, five years after incorporating as a village, a lively community of hotels, shops and factories sprang up along the Erie Canal’s banks and paralleling the Genesee Turnpike, at what is now Clinton Square. Syracuse incorporated as a city, merging with nearby Salina, in 1847.

As Syracuse’s salt industry declined after the American Civil War, the city’s economy moved toward manufacturing, and the skilled hands of the city’s machinists produced traffic lights, specialty electric items, typewriters, the famous Franklin Car, and more. Syracuse was also home to the Craftsman Workshops, the center of Gustav Stickley’s handmade furniture empire.

The area’s vast limestone and salt deposits were turned to the manufacture of soda ash by William Cogswell and his Solvay Process Company in 1884. Soda ash is tremendously important in many industries and is used in making such diverse items as glass, laundry washing soda, textile dyes, food additives, toothpaste and bricks. The Solvay Process Company was a major employer in the region for almost 100 years, only closing it doors in 1985, after the discovery of major deposits of sodium carbonate in Wyoming rendered the Solvay process economically infeasible. However, as a result of this century-long occupation, Lake Onondaga had become seriously polluted, and has not recovered yet.

By 1839, the Syracuse and Utica Railroad came to the city, laying tracks down Washington Street, which was then the main street of the village. The Syracuse and Utica was one of the many smaller railroads eventually incorporated into the New York Central, and the NYC’s right of way came to run over the canal’s towpath, even as the canal was later filled in to create Erie Boulevard. The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western (DL&W) Railroad was the other major railroad that came through Syracuse, maintaining its own stations.

Initially, of the multitude of railroad tracks in the city were at street level, and by 1898, this situation was becoming intolerable, with traffic congestion in the center of the city and many injuries and fatalities resulting from the mix of steam engines and trains, pedestrians, horse-drawn vehicles—and soon enough, automobiles. Thus the city leaders began an effort to elevate the tracks through the city. Both the NYC and DL&W elevated 35 miles of tracks within the city, including 27 bridges over busy intersections, in an enormous effort costing $17 million in 1936 dollars. This project finished with the opening of the new NYC station. The city held a four-day Jubilee to mark the event with civic dinners, parades and other festivities. At the time it opened, the new Art Deco station, which still proudly displays a carved relief of a locomotive at its entrance, served 100 trains a day.

In nearby East Syracuse, the NYC established the huge DeWitt Railyard Complex in the 1870s. The DeWitt yard was one of the busiest yards in the world for many decades. Most of the village of East Syracuse worked in the railyards when it was incorporated in 1881. The DeWitt Yard is still a major intermodal freight yard operated by CSX, successor to the NYC. The operation is now largely used to sort container trains going to and from the west coast and points east.

While Syracuse’s downtown still retains a number of architectural beauties, such as the former NYC station, perhaps the most iconic and representational of its golden age is the Niagara Hudson Building, often referred to locally as the Niagara Mohawk Building. Built in 1932, it was designed by the Buffalo architectural firm of Bley & Lyman and the Syracuse architect Melvin L. King; and housed the headquarters of the Niagara Mohawk power utility company, which in those days styled itself as the “nation’s largest electric utility company.” This building is one of the best examples of the Art Deco style in New York State, and some say in all of America. The dramatic seven-story structure’s façade is constructed of gray brick and stone in a series of setbacks, with additional cladding in stainless steel, aluminum, and black glass. The ornamentation on the building is opulent, featuring parallel bands, zigzags, and chevrons. At the base of the tower, six stories above the entrance, a twenty-eight foot statue of a male figure floats, arms outstretched, from which rays of light emanate like gigantic wings; the sculpture is called, “Spirit of Light.” By night, the building gleams and shimmers under powerful outdoor floodlights and interior lights.

As with other central New York cities, Syracuse is seeking to restore not only its architecture but its progressive spirit. In 2001, then Governor Pataki established a program to create five “Centers of Excellence” across the state to leverage hundreds of millions of dollars of private investment and thousands of new jobs. As a result, the NYC station has a new neighbor in the recently-opened Syracuse Center of Excellence (COE). The city’s new COE houses the Environmental Quality Strategically Targeted Academic Research Center, whose mission is to include, beyond economic development, renewable and clean energy sources from wind and solar power to geothermal and fuel cell technology. The COE itself has an intermodal transportation center under construction on its campus to provide parking for vehicles, charging stations for electric vehicles, a bus shelter, bike shelter, and vending machines. Additionally, green infrastructure will send storm water from the site and the adjacent streets to rain gardens and tree wells on-site; and the project will make use of innovative paving and building materials.

Amtrak provides both ticketing and baggage services at the Syracuse station, which is served by eight daily trains. Empire Service trains are supported by funds made available by the New York State Department of Transportation.”